The theory is over. As the first commercial tanker of Green Ammonia departs the Port of NEOM for Rotterdam this week, the “Energy Transition” has officially moved from a PowerPoint presentation to a balance sheet. Here is the economic reality of the 2026 hydrogen market.

By [Your Name] | The Telegraph Middle East Published: January 10, 2026

For the past five years, “Green Hydrogen” was the buzzword of every energy conference from Davos to Abu Dhabi. It was the “fuel of the future”, promising, clean, but perpetually five years away from profitability.

This week, the future finally docked.

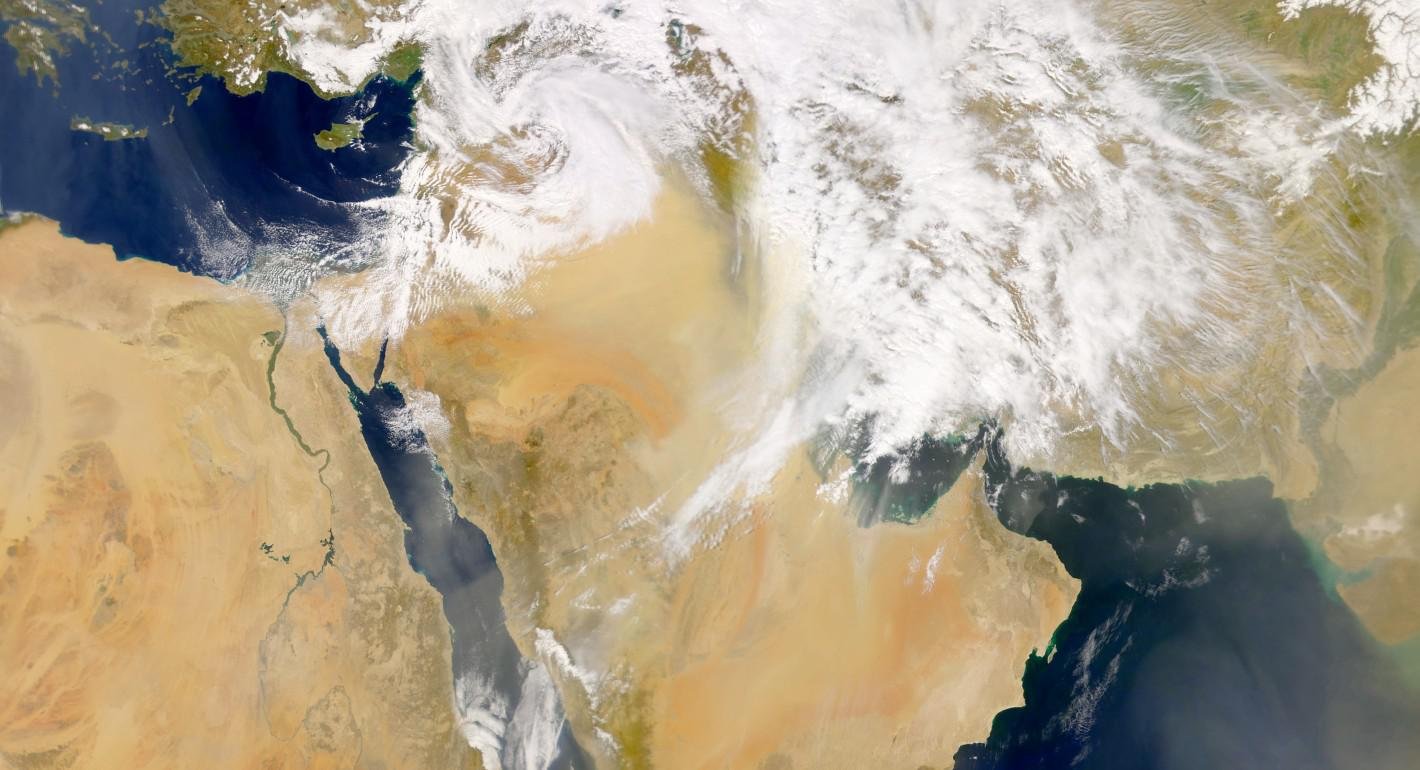

In a historic milestone for Saudi Vision 2030, the NEOM Green Hydrogen Company (NGHC) has officially commenced commercial export operations. The tanker Helios One is currently navigating the Red Sea, carrying 25,000 tonnes of “Green Ammonia” destined for the Port of Rotterdam in the Netherlands.

This is not a pilot project. It is the first installment of a 30-year operational cycle from the world’s largest utility-scale hydrogen plant. For the energy markets, the departure of this ship answers the biggest question of the decade: Can the Middle East replace its oil barrels with hydrogen molecules?

The “Helios” Reality: Scale vs. Cost

The NEOM green hydrogen export 2026 milestone is significant because of the sheer scale involved. The Helios plant, powered by 4GW of solar and wind energy, produces up to 600 tonnes of carbon-free hydrogen per day.

However, the critical story for investors is not the chemistry; it is the cost curve.

In 2022, producing green hydrogen cost upwards of $5.00 per kilogram—nearly four times the price of “Grey Hydrogen” (made from natural gas). Critics argued it would never be competitive without massive subsidies.

Today, in 2026, NEOM has reportedly achieved a production cost nearing $2.50 per kilogram.

“We are seeing the ‘Solar Effect’ repeat itself,” explains Dr. Heinrich Weber, an energy economist based in Berlin. “Just as solar power costs collapsed in the 2010s due to scale, electrolyzer costs have plummeted by 40% since 2023. NEOM’s advantage is that it has the cheapest solar hours on earth. They are effectively exporting sunlight in liquid form.”

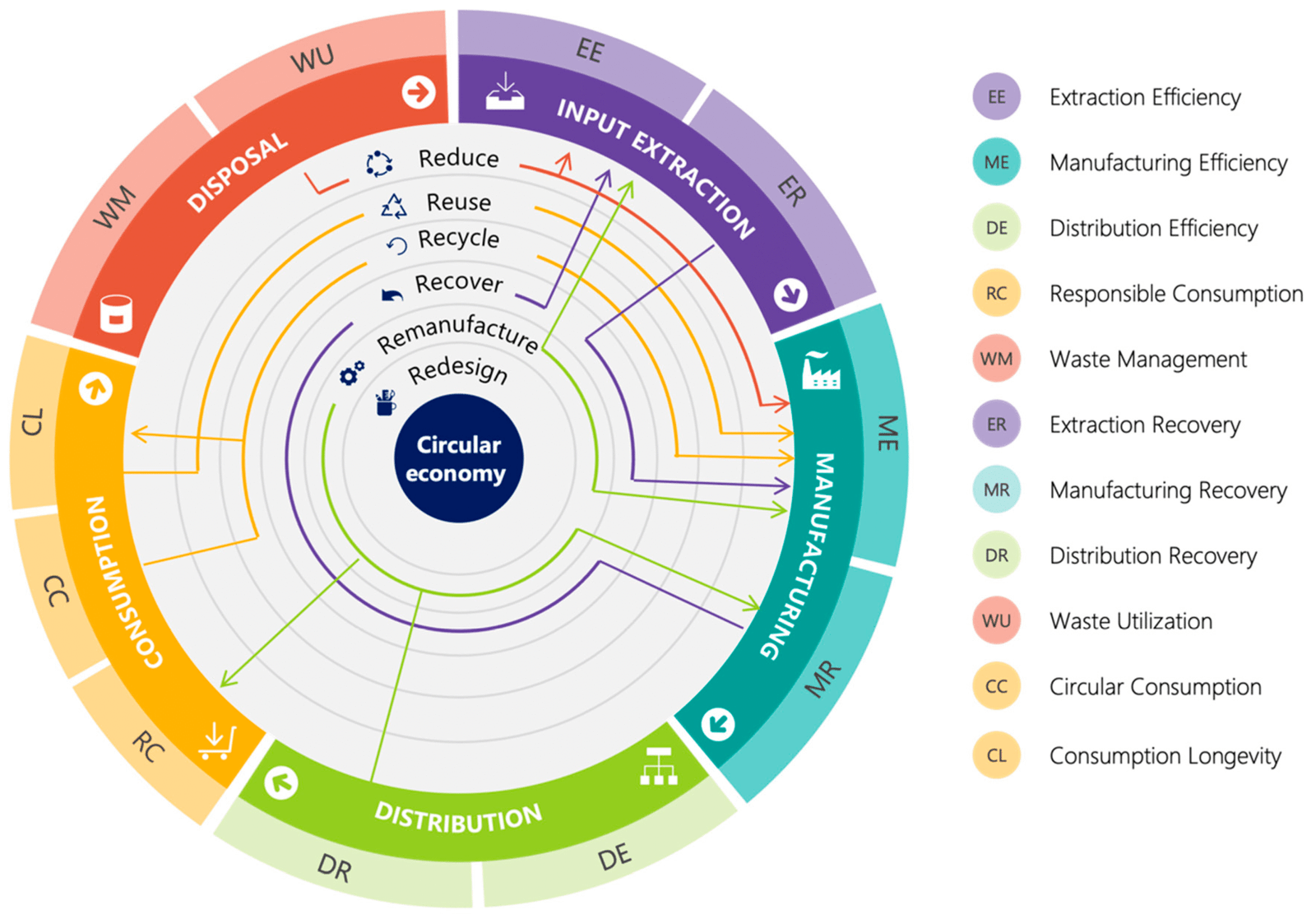

Why Ammonia? The “Trojan Horse” of Energy

A key confusion for the public is why the NEOM green hydrogen export 2026 initiative is shipping ammonia, not pure hydrogen.

The answer is physics. Hydrogen is notoriously difficult to transport; it must be cooled to near absolute zero (-253°C). Ammonia (NH3), however, turns into a liquid at a manageable -33°C and contains a high density of hydrogen.

NEOM is using ammonia as the carrier. Upon arrival in Rotterdam, the cargo will either be used directly as fertilizer and maritime fuel or “cracked” back into pure hydrogen to power heavy industry in the Ruhr Valley.

Read More: GCC Wealth Transfer 2026: Why $1 Trillion is Leaving Real Estate

The “CBAM” Factor: Europe’s Hidden Subsidy

The economic viability of this shipment is heavily supported by European policy—specifically, the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM).

As of 2026, the EU effectively taxes imports based on their carbon footprint. Steel and chemical manufacturers in Germany are desperate to decarbonize to avoid these penalties. This has created a “Green Premium.” They are willing to pay more for NEOM’s green molecules than for cheap Russian or American gas, because the tax savings offset the higher fuel cost.

This regulatory alignment has made the NEOM green hydrogen export 2026 strategy commercially solvent years earlier than skeptics predicted.

The Competition: It’s Not Just Saudi

While NEOM has the “First Mover” advantage, the race is crowded.

The UAE is close behind. ADNOC’s low-carbon ammonia production facilities in Ruwais have already secured offtake agreements with Japanese power giants like MITI. Oman, too, has aggressively positioned its Duqm port as a hydrogen hub.

However, Saudi Arabia’s sheer land mass gives it an edge. The Kingdom has allocated areas the size of Belgium solely for solar panels to power these electrolyzers. It is an industrial ambition that few other nations can physically match.

Read More: UAE Digital Dirham 2026 Rollout: Is This the End of SWIFT for Gulf Trade?

The Geopolitical Pivot

For Riyadh, this tanker represents more than just a commodity sale. It is a geopolitical pivot.

For 80 years, the Kingdom’s strategic importance was anchored in the security of oil supply. By becoming the primary supplier of green energy to a decarbonizing Europe, Saudi Arabia is ensuring its relevance for the next 80 years.

“The molecule changes, but the map stays the same,” notes a geopolitical risk analyst in London. “Europe needed Gulf oil in 1970. It needs Gulf hydrogen in 2026. The dependency remains.”

What’s Next: The Pipeline Dream?

While ships are the current solution, the long-term vision is even bolder. Discussions have revived regarding a potential hydrogen pipeline connecting the Eastern Mediterranean to Greece—a physical umbilical cord of energy.

For now, all eyes are on the Helios One. When it docks in Rotterdam next week, it will unload the first tangible proof that the post-oil era has actually arrived.